Why is AI the new Duchamp urinal?

Thinking about artificial intelligence and the future of design, I want to recall one of the most iconic moments in Modern Art history.

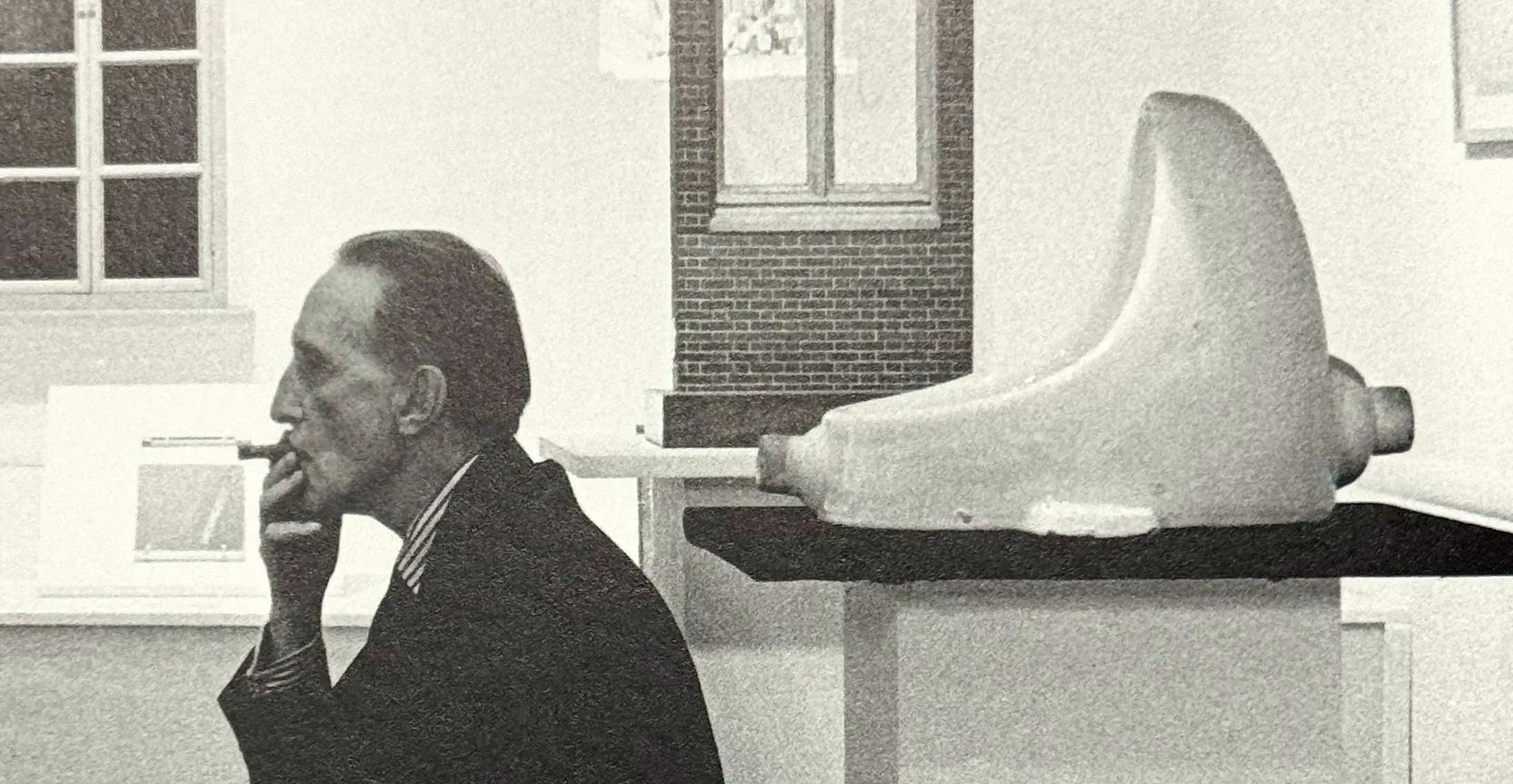

A little over 100 years ago, Marcel Duchamp submitted his famous Fountain — an urinal that he bought at a hardware store and signed with a pseudonym — as an artwork to the Society of Independent Artists exhibition in 1917. It was a group of new, young, progressive, free-thinking artists who challenged the conservatism and a certain tackiness of the art market at the time.

With this work, Duchamp inaugurated an art category called ready-made; made with ready-made, already existing objects that are placed in a new context¹. Duchamp said that the execution of the work, in any technique — the act of painting an oil canvas or carefully sculpting a block of marble — has no value in itself. The most important thing is the idea; not its execution. An idea was enough, and a ready-made object, in a new context.

AI as the new readymade factory

Ready-made objects, or objects just seconds away from being ready, are the great novelty that generative AI offers us. Texts, images, and videos, whatever you can imagine, just ask, and it delivers. And it delivers as many variations as you want. The first boss I had in life, Jacira, at an advertising agency, used to say: “Fabio, client taste isn’t debated, it’s lamented”. AI vomits whatever you want from it.

What are we going to do with the dozens or hundreds of versions that AI delivers to us? Our role is gaining a curatorial component. Let’s focus here on the second part of Duchamp’s idea: a ready-made object placed in a new context. For us creatives, context is the macro vision of the problem. It’s understanding the client, their history, their origin, their challenges, their audiences, the pain points of these audiences, market dynamics; it’s understanding changes in culture, in people’s behavior — that’s the context. And it’s in this, in this more horizontal vision that connects different areas of knowledge; having empathy and being able to understand what isn’t necessarily explicit, requested in a prompt… knowing how to weave all this together; this is a skill of ours, human, that AIs have less chance of replacing us in.

Market reality: quality vs. zero cost

It’s true that, for the market as a whole, it won’t be easy. Many companies will be satisfied with what AI will generate for them. If the result is 50% of the quality that a professional would do, but at almost zero cost and with immediate delivery, I fear that many managers will choose this. We lament, as my boss used to say — it will become cliché, tacky, boring —, but there’s no point in arguing about it.

The artists’ revolt: history repeating itself

The artists in Duchamp’s time were also furious with him. The urinal was considered indecent even by those young progressive rebels and didn’t even get to be displayed in the official gallery of the exhibition. The famous photo we know of it was taken only two days later. The original urinal was lost. Some say it was destroyed by members of the organizing committee. Because Duchamp’s submission also meant that, from then on, anyone could be an artist. Just a ready-made object, in a new context. What do you mean? And I who spent years learning to paint, to sculpt, training every day… What do you mean, anyone can now make art?

It’s a reality we have to deal with, again. But, calm down.

I don’t know if I would be a font designer today if I had to polish small lead blocks like in the past, like a goldsmith works with jewelry. I don’t think I would have that skill. I don’t even draw well, and my handwriting is horrible. I was so relieved when I learned that one of my great idols in typography, Matthew Carter (he designed Verdana), tells that his handwriting is also horrible. He doesn’t know how to draw. He’s an impressive designer, versatile, very detail-oriented. And it’s okay not to know how to draw by hand. There’s a mouse. Technique by itself, execution, is losing value.

What research reveals about AI and creativity

A study² came out from the University of London with almost 300 people to evaluate creativity, with and without AI help. What they identified is that AI increases the creativity of those who aren’t creative, but doesn’t bring benefits (and sometimes hinders) those who are already creative. It doesn’t take us to new levels, but it lifts up those who are mediocre.

I believe that AI will solve those projects that have low added value, but exist in large quantities, but it won’t replace what only we, you and I, humans, have to offer.

On the Cannes Lions³ stage, the CEO of Publicis group said that it will be up to us to have the ‘big ideas’, in his words, and beside him on stage, the CEO of Adobe promises that the tools will execute them with unprecedented ease in history. We’ve been seeing this. AI being a way to materialize (and also democratize) the execution of ideas. I’m skeptical about the final quality, the detail, the craft of what AI delivers, but if there’s something constant in the history of all technologies is that they start like this: bad, we think it’s ridiculous, but over time they improve, incrementally, the cost goes down, they become popular and get even better, to the point of creating a true revolution. And we’re living through one now.

Advice for surviving the revolution

My advice to all designers, and creatives in general, is to focus on what we know AIs have less chance of replacing us in. Instead of a specific technical skill, it’s about having a macro perspective on problems, connecting different areas of knowledge.

It’s about having good taste, repertoire, having empathy, feeling the moment and people as the complex and irrational individuals we are.

¹ GOMPERTZ, Will. What Are You Looking At? Penguin Books, 2012

² DOSHI, Anil & HAUSER, Oliver. Generative AI enhances individual creativity but reduces the collective diversity of novel content. Science Advances Vol 10 No 28, 2024

³ NARAYEN, Shantanu & SADOUN, Arthur. The New Creative Frontier. Cannes Lions Festival, 2025

Cover photo by Julian Wasser. MINK, Janees. Duchamp. Taschen, 1995